Japan's Food Waste Problem

Why and where food gets wasted in Japan, and what's being done about it.

📣 Hello readers: If you enjoy today’s newsletter, please share the love and click the 💟 “Like” button at the bottom of this page!

If you have suggestions for us, please click the 💬 “Comment” button too. Your feedback helps us bring you more of the nutritious news you’re hungry for.

About us: MarketShake is curated by GourmetPro. We help F&B brands and companies expand globally by providing bespoke matching to our exclusive network of local consultants. Wherever you’re exploring opportunities in F&B, GourmetPro has the perfect local expert to guide you. Explore our services.

Happy Tuesday Market Shakers. Today begins our new cycle about upcycled food and beverages. Before we delve deep down into the burgeoning market for upcycled products, and what upcycling even is exactly, we’re going to explore the food waste crisis that is driving the trend!

For this post, we’ve rooted through the freshest information on waste and upcycled it into an easy-to-digest report. Let’s dig in!

Summary of today’s content

The global food waste crisis

Food waste in japan: a Mt. Fuji sized problem

Unsustainable food and beverage industry policies

Cultural contradictions

Japan’s food waste fighters

A solution on the up

The Global Food Waste Crisis

In 2011, the United Nations reported that almost one third of all food produced globally goes to waste. That’s 1.3 billion tonnes of food, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s 2021 estimates.

The reasons for large scale food waste are complex. In developing countries, most food waste is reported to occur at the production and supply chain level; here underdeveloped storage and transportation infrastructure results in losses. In wealthy countries, however, food waste is driven by retailers and consumers who toss food because they over-ordered, or because the food fails to meet aesthetic standards.

This colossal food waste crisis is rubbish news for us and our planet on many levels. To start with, while so much food is wasted, an estimated 820 million people went hungry in 2018. The amount of food currently being wasted is enough to feed that number four times over.

Wasted food isn’t just bad for world nutrition, it’s bad for the environment, and our pockets too. Food that ends up on the trash heap releases methane as it rots, which is why the current global carbon footprint of food waste is estimated to be 10%. This is more than the combined car exhaust emissions from the U.S. and Europe, according to the WWF.

There’s also the cost of disposing of mountains of waste. In the U.S. alone, the cost of disposing of wasted food is an estimated $218 billion, or $1,800 per household. When you factor in all the time, effort and money that goes into production and supply chain too, the total cost of food waste is staggering.

Time to take back the trash

In order to tackle these problems, the UN set as a sub-target for SDG no. 12, a 50% reduction of global food waste by 2030. They also urge taking action to reduce both food waste: food lost from production up to (but not including) retail, and food loss: food lost at retail and consumption.

This has galvanized countries to invest in initiatives to reduce food loss and waste. The U.K., for example, has been most successful in reducing food waste per capita, achieving a 27% decrease so far between 2018 and 2021, through reforms to both household and supply chain waste management.

Many countries have already implemented policies seeking a 50% reduction to food loss and waste by 2030 in line with the UN SDGs. Participating governments are doubling down on efforts to support initiatives and companies who contribute to solving the problem. The Canadian government, for example, has earmarked over $10 million for investment in companies working towards reducing food waste and loss.

Food and beverage companies are facing increasing pressure from investors and governments alike to tackle the food waste crisis. This has translated into companies’ ESG and CSR KPIs. In 2020, Kraft Heinz committed to a 20% reduction in food waste across all manufacturing facilities by 2025. Similarly, Nestle is aiming for a 50% reduction to their wasted food by 2030. These targets are helping to drive innovation within big businesses as well as investment in startups that offer creative solutions to this urgent problem. U.S. grocer Kroger is just one company that has pledged money to invest ($2.5 million) in startups tackling food loss and waste.

There’s a lot of activity already being taken to reduce food waste, and the story in Japan is no different. Let’s see how the country fairs in terms of food waste and progress towards reduction.

Food Waste in Japan: a Mt. Fuji sized problem

According to government data, Japan wasted 6 million tonnes of food in 2018 that was fit to eat. The recent estimate from the U.N. puts waste in 2021 at over 8 million tonnes. Unwanted food is burning a hole in Japan’s landfills and also consumers’ pockets, as disposal is costing an estimated ¥2 trillion annually.

But how can Japan, a country where the concept of mottainai, regret over waste, is so deeply ingrained in the culture, be one of the world’s largest food wasters? Food and beverage industry policies, and, as is often the case in Japan, culture, are important factors in the equation.

Unsustainable food and beverage industry policies

“The one-third rule” was introduced by Japanese retailers in the 1990s in response to demands from customers for only the freshest products. The rule requires producers or wholesalers to deliver foods and beverages to retailers in Japan within the first third of the period spanning from the production date to the expiration date. This is stricter than similar rules applied in other developed countries. Any food delivered after the first third of this period can be returned or thrown away.

The rule results in vast amounts of edible food being binned in Japan, according to a government report. In fact, a massive 33% of food designated for sale at retail never ends up reaching consumers.

Cultural contradictions

Stringent quality policies aside, over-obsession by consumers themselves about food safety is also a big driver of food waste in Japan.

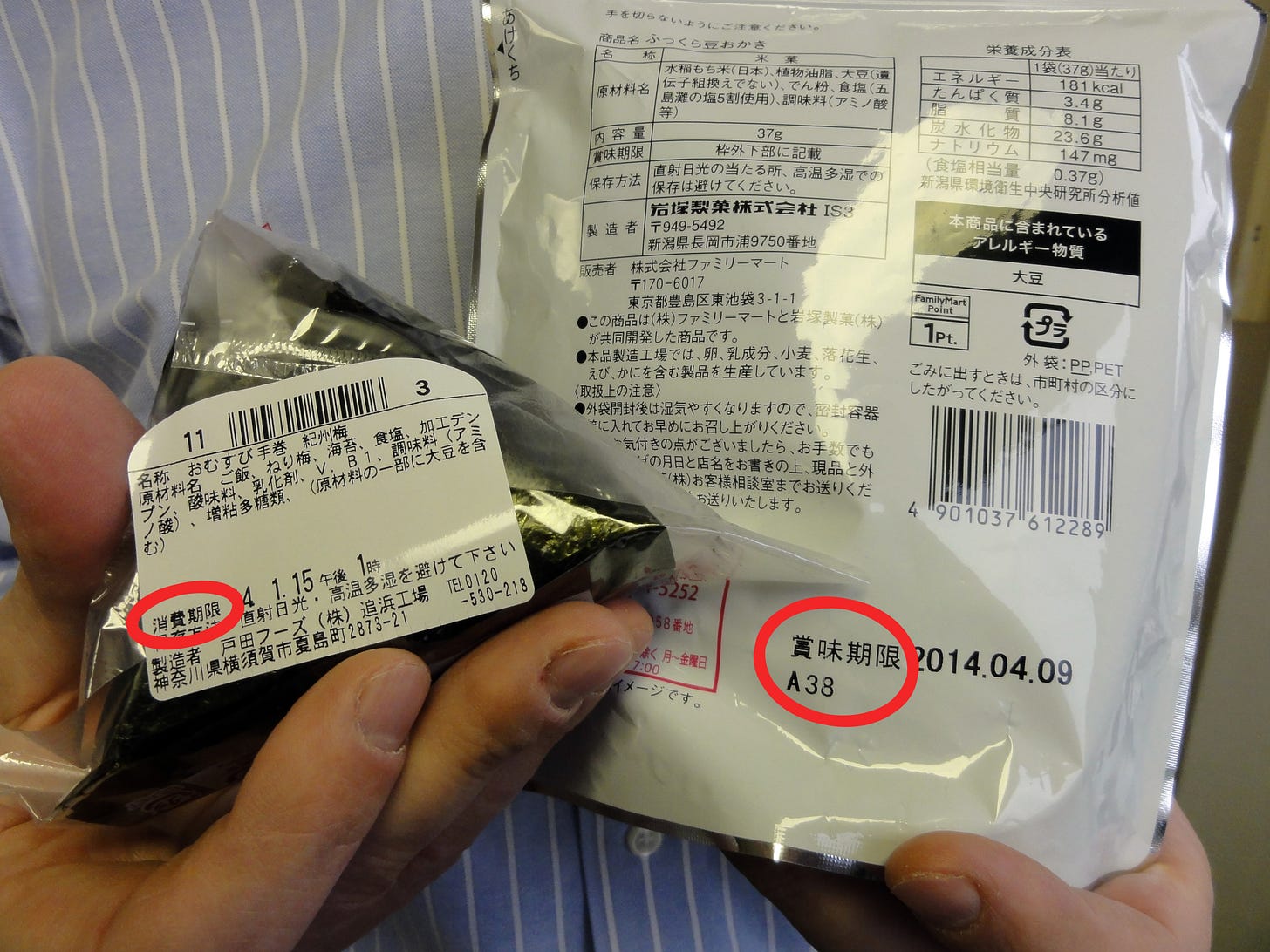

46% of food waste in Japan is estimated to come from households. A large amount of this is believed to result from a lack of awareness about different types of expiry dates on products. In Japan, products have two separate dates for suggested consumption: "taste best if used by" and “recommended to consume by” dates. Experts agree that the “taste best if used by” date is set much earlier than necessary, with foods generally being edible for weeks after the suggested date. Despite this, many consumers are confused by the two dates and end up wastefully binning foods by the first date.

Adding on to this is the concept that ‘‘fresh is best”, which also drives potentially wasteful shopping practices in Japan. Most Japanese consumers will select products by their latest expiration date when shopping. As a result, older products pile up and must eventually be thrown away by stores.

The same commitment to only the freshest foods haunts restaurant refuse too. In part due to the scorching summer temperatures that soon spoil food, the idea of doggy bags - taking home uneaten food after eating out, has not caught on in Japan. Restaurants fear the backlash from cases of food poisoning that may result from food spoilage while customers take it home. So, they don’t offer doggy bag style services and refuse when customers inquire, leaving the leftovers for the bin.

A preference for aesthetically pleasing produce also means many consumers in Japan show no love for blemished or asymmetrical foods. As a result, companies throw away a large amount of differently shaped fruits and vegetables rather than send them to retailers. Any imperfect products that do make it too stores are still destined for the dustbin as consumers will likely overlook them for more shapely items.

All this has resulted in some Mt. Fuji sized piles of rotting food filling up Japanese landfills. The fact that something is off has attracted concern from several parties.

Japan’s food waste fighters

The Government

The Japanese government and companies are taking steps to reduce food loss and waste in Japan. The Japanese Diet passed the Act on Promotion of Food Loss and Waste Reduction in 2019. The act sets a target to cut national food waste in half by 2030 in line with the UN SDGs, and requires municipal governments to implement supporting initiatives.

Towards this, the government has already taken steps such as relaxing the “one-third rule” so retailers accept products delivered in the first half of their life before expiration. They have also encouraged changes to product expiration dates, suggesting only year/month be displayed, rather than the current year/month/day, in a step towards reducing delivery rejections.

Companies are starting to do their bit too

Several companies have also stepped up to help reduce food loss in Japan. Sustainability minded convenience store chain Lawson has implemented AI technology to align their store’s supply with consumer demand. The technology is from US firm Data Robot and uses AI to ensure Lawson doesn’t overstock their shelves. Competitor Seven-Eleven has also piloted programs where customers earn points that can be converted into e-money when they buy products close to expiry.

Other companies like Suntory Beverage & Food Ltd. have also implemented tech to battle food waste during production. Suntory is using AI to identify how products get damaged during transportation so they can eventually reduce the number of products returned by 30 - 50%.

A growing number of startups are also offering solutions that help save food from being wasted. CoCooking, a company whose app, TABETE, connects restaurants that have excess food nearing expiry with customers and people looking for food, has attracted investment. From this we can see the appetite for saving food is definitely hotting up in Japan.

Despite efforts, however, food waste remains a problem in Japan. With over 8 million tonnes of food estimated to be wasted in 2021, much more needs to be done to fight this growing crisis.

One of the most promising solutions to Japan’s food waste problem is the emerging trend toward upcycling food and beverages. In recent years, Japan has seen the rise of startups and companies seeking to turn waste into value-added new food products.

But just what is upcycling and why is the market for upcycled products burgeoning across the world?

The low-down on upcycling

Upcycled foods, according to the UPcycled Foods Association, prevent food waste by making entirely new products out of foods that would have otherwise been thrown away. Rescuing wonky vegetables that are considered too hideous for store shelves and turning them into soups, for example.

Despite the market for upcycled foods currently being worth $46.7 billion, with an estimated 5% CAGR over the next 10 years, awareness about upcycling in F&B is still low. For example, a study published in the Food and Nutrition Sciences found that only 10% of consumers are familiar with upcycled food products.

With that being said, interest in upcycling is mounting faster than the piles of waste the process seeks to prevent. In recent years we have seen an explosion in the number of startups that are using upcycling technology to fight food loss and waste. Singapore’s Crust, Canada’s Outcast Foods, and the U.K.’s Rubies in the Rubble are just a few examples of startups making a difference to what we eat with ingredients that were destined for the dustbin. Likewise, big businesses are jumping on the bandwagon too, like U.K. brewer BrewDog, who recently launched a vodka produced from their bad beer.

But upcycling is far from just ‘the latest trend’. The whole goal of the upcycling movement is to transform the way we look at ingredients for our food so that we waste less while making more to feed hungry mouths.

Successfully integrating upcycling practices into our food system could result in saving 1.3 billion tonnes of food each year, reducing global greenhouse gas emissions by anything between four to eight percent. This potential is drawing players from around the world into an exciting new food and beverage market, including those in Japan.

Upcycling in Japan

There’s a ton to talk about when it comes to turning tonnes of gomi (the Japanese word for trash) into gourmet in Japan. From traditional companies who have been upcycling since before it was cool, to new startups who are taking waste and transforming it into beers, chocolates, and even granola, there’s a lot to learn and be excited about.

For the next few weeks, we’re going to break down the upcycled food and beverage market globally and in Japan. As usual, we’ll bring you the voices of real consumers, on the ground overviews of product availability in Japan, and insights from experts who are making waves in the upcycling market. So, keep an eye on your inbox, and see you next Tuesday!

Made with ❤️ by GourmetPro - your network of on-demand Food & Beverage experts.

💌 If you have any questions, you can directly answer this email. We read and answer all messages.

💖 And if you think someone you know might be interested in this edition of Market Shake, feel free to simply forward this email or click the button below. 💖